Imam Abdullah al-Haddãd, the creator and writer of the Rãtibul Haddaad, was born into a devout family. Despite becoming blind at the age of three, he wrote numerous influential books and delivered lectures that significantly contributed to the spread of Islam globally. Remarkably, his lack of physical vision seemed to be compensated by a profound spiritual insight.

During an era marked by relentless political upheavals impacting the Muslim world, both from within and externally, causing widespread instability, Imam al-Haddãd remained steadfastly committed to his spiritual path. His intense spiritual journey began early in his life and continued until he passed away at 88. A notable figure in the Bã’Alawiyyah Sufi Order (tariqa), Imam al-Haddãd was also a descendant of Prophet Muhammad (SAW).

Expansion of the Rãtibul Haddaad

Among the various litanies and poems authored by Imam al-Haddãd, the Rãtibul Haddaad stands out as a significant form of dhikr (remembrance of God). The mission (da’wah) led by Imam al-Haddãd and his descendants played a crucial role in the swift expansion of Islam in nations like Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei, and southern India.

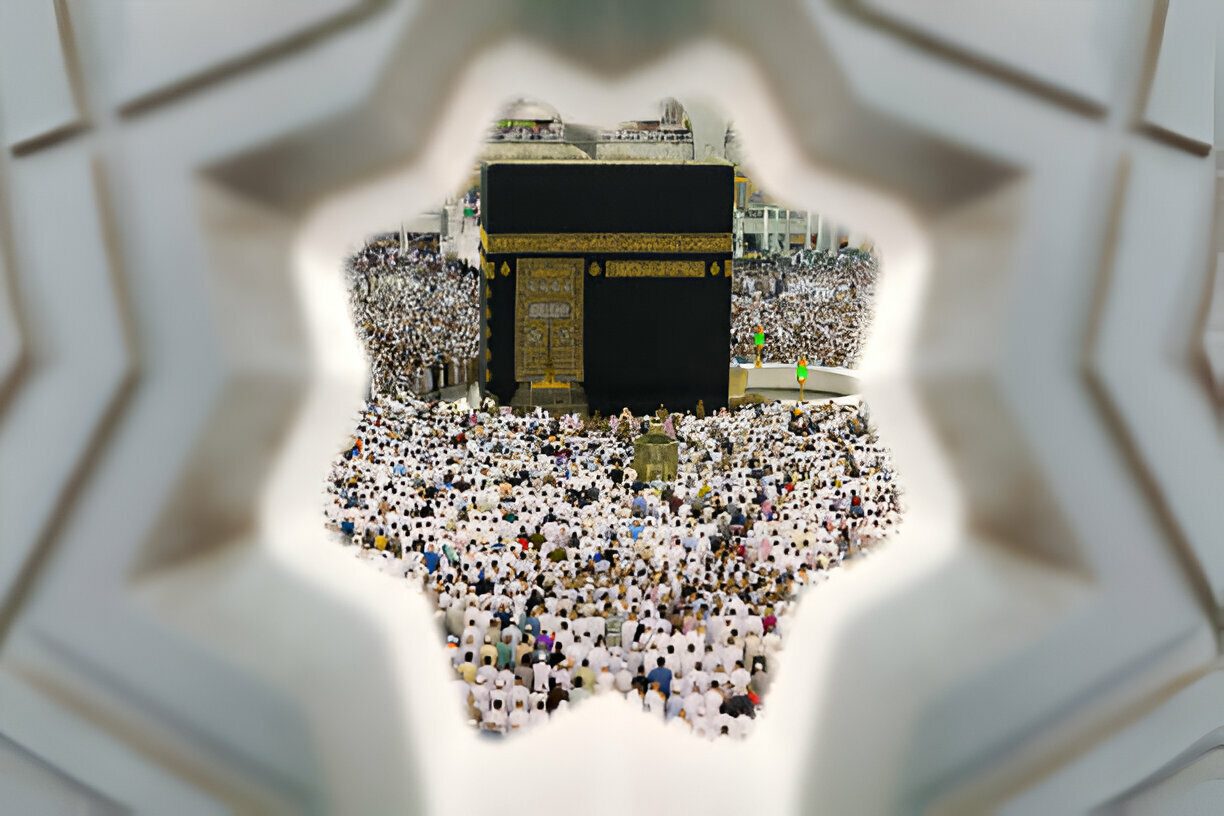

Conceived through divine inspiration, the Rãtibul Haddaad was developed at a time when Imam al-Haddãd was at his intellectual and spiritual zenith. The Rãtibul Haddaad was first introduced during the Imam’s Hajj pilgrimage and quickly spread across various countries. Imam al-Haddãd emphasized that the recitation of Rãtibul Haddaad served as a protective measure for towns and cities and was beneficial for those seeking divine assistance for specific needs.

The Recitation

The Rãtibul Haddaad customarily begins with a preamble that includes

Sūrah Yãsīn, Sūrah al-Mulk, and the Asmã ul Husnã, followed by the start of:

Sūrah al-Fãtiha

It is reported that the Prophet (SAW) stated that Sūrah al-Fãtiha, which

has seven oft-repeated verses is the greatest Surah in the Quran.

Ãyãt al-Kursī

In a hadith, the Prophet (SAW) mentioned that for Muslims who recite Ãyãt al-Kursī before sleeping, Allah will assign a guardian to watch over them throughout the night.

Sūrah al-Baqara (last two verses)

It is reported that the Prophet (SAW) said that if someone recites the last two verses of Sūrah al-Baqara at night, it will be sufficient for them.

There are about 25 clearly discernible segments, including supplications like:

O Allah! Grant us excellent steadfastness; reliance on You alone; grant us wisdom and beneficial knowledge; and bless us.

O Allah with lawful and wholesome sustenance, without any hardship or difficulty.

O Most Generous and Bountiful grant us a good ending, without any trials

or tribulations.

The Rãtibul Haddaad has been discussed and translated into English by a number of South African Muslim scholars, including Shaykhs Abdullah Abduraouf, Ismail Ganief, Taha Gamieldien (handwritten version) and Amien Fakier. The latest publication was by Professor Ghoesain Mohamed, who sadly passed on.

Shaykh Yusuf

The origins of Rãtibul Haddaad in the Cape are not definitively established, but several historians believe that Shaykh Yusuf of Macassar was responsible for its introduction. Of noble Indonesian descent, Shaykh Yusuf was exiled to the Cape in 1693. While he wasn’t the first Muslim to arrive at the Cape, he is widely recognized for establishing Islam there. His exile was due to his leadership in military opposition against Dutch colonial forces. Shaykh Yusuf left for Makka in 1644, spending around 20 years studying under various esteemed scholars.

Some believe Shaykh Yusuf met Imam al-Haddãd and directly learned Rãtibul Haddaad from him. However, historical records suggest that they could not have met during 1669, the year Imam performed Hajj.

Shaykh Yusuf’s Impact at the Cape

The Dutch’s effort to isolate Shaykh Yusuf by settling him at “Zandvliet” farm was unsuccessful. Instead, Shaykh Yusuf’s residence became a hub for “fugitive” slaves and other exiles, leading to the formation of South Africa’s first cohesive Muslim community. The area around Zandvliet is now known as Macassar, a nod to Shaykh Yusuf’s origin.

Religious Restrictions and Shaykh Yusuf’s Role

At that time, Dutch laws (placaaten) at the Cape strictly prohibited the practice of any religion other than the Dutch Reformed Church’s teachings. The punishments for practicing Islam were harsh, including physical mutilation or death. Slaves often faced brutal treatment, being considered property of their owners. However, due to his royal background, Shaykh Yusuf was treated with respect and managed to secretly conduct Islamic lessons for fugitive slaves and free Blacks.

The Background of the Laagu

In a context where the spread of Islam was prohibited, Shaykh Yusuf ingeniously incorporated a melody (laagu) into the chanting of the Rãtibul Haddaad. This creative adaptation was a strategy to circumvent the ban on Islamic propagation. Given that singing was a prevalent activity among the slaves, they could perform the Rãtibul Haddaad using laagu. This approach misled the Dutch authorities and soldiers into believing that the slaves were simply engaging in regular singing. Despite the restrictions on Islam, a significant number of fugitive slaves and local inhabitants came to embrace Islam under the guidance of Shaykh Yusuf.

Sayyid Alawi

Several historians believe that Sayyid Alawi was responsible for introducing Rãtibul Haddaad in the Cape. Originating from Mocca in Yemen, he came to the Cape in 1774. The Dutch exiled him there, condemning him to lifelong imprisonment in chains. The Dutch authorities labeled him a “Mohammedan Priest.” He spent 11 years in chains on Robben Island, after which he moved to Cape Town upon release. Notably, he engaged in active da’wah with the slaves at the Slave Lodge.

Later, he served as a policeman, a role that allowed him unrestricted access to the Slave Lodge. He is widely acknowledged as the first “official” imam at the Cape and rests at the Tana Baru cemetery. The likelihood that Sayyid Alawi introduced the Rãtibul Haddaad at the Cape is high, considering his affiliation with the same tariqa as Imam al-Haddãd, the Ba’Alawiyya tariqa. In contrast, Shaykh Yusuf belonged to the Khalwatiyya tariqa, and it would be uncommon for a member of one tariqa to adopt the litany of another tariqa.

Slavery and Singing

The practice of music and singing was a widespread phenomenon among slaves around the world, serving as an outlet for their emotions, be it grief or happiness. For instance, African slaves in the United States and Europe often engaged in singing gospel songs.

Similarly, many of the initial Muslim converts were associated with a Sufi tariqa, where reciting dhikr with a laagu is a traditional practice. Consequently, the chanting of the Rãtibul Haddaad with a laagu was not uncommon. This recitation, whether done solo or in a group, with or without a laagu, persisted for over 300 years, spanning from the colonial era through Apartheid and into the democratic era.

Following the grant of religious freedom in 1804 and the abolition of slavery in 1838, the Muslim population experienced a significant increase. By 1842, they constituted over two-thirds of the population in the Cape. The swift spread of Islam was greatly influenced by the devout and courageous Orang Cayen (Muslim political exiles), including figures like Shaykh Yusuf, Tuan Guru, and Sayyid Alawie.

The Ratibul Haddad History and Evolution

Like African slaves in the USA and Europe who often expressed their emotions through gospel songs, early Muslim pioneers, commonly associated with a Sufi tariqa, frequently practiced dhikr with a laagu. It’s common for the Rãtibul Haddaad to be recited in this manner.

This tradition of reciting the Rãtibul Haddaad, either individually or in groups, with or without a laagu, persisted over 300 years, through the colonial and Apartheid eras, into democracy. After the grant of religious freedom in 1804 and the abolition of slavery in 1838, the Muslim population surged, accounting for over two-thirds of the Cape population by 1842. The spread of Islam was significantly influenced by devout and courageous Muslim political exiles like Shaykh Yusuf, Tuan Guru, and Sayyid Alawie.

By the early 1800s, this ritual evolved into what was known as a gadat, typically performed at a merang on the 7th, 40th, and 100th days following a death. These gadat gatherings were communal, featuring special food and inclusive of children’s participation.

Reciting the Rãtibul Haddaad connects us to the universe, at the core of which is the atom, constantly engaged in dhikrullah. Dhikr has the power to heal both heart and body, paving the way to receiving the Divine Message. As highlighted in Surah al-Ra’d, Allah states: “Those who believe, and whose hearts find satisfaction in the remembrance of Allah; for without doubt, in the remembrance of Allah do hearts find satisfaction.” (Surah 13, verse 28)

Imam Al-Ghazali and Bidayat al-Hidayah” (The Beginning of Guidance)

Imam Al-Ghazali, in his works, including “Bidayat al-Hidayah” (The Beginning of Guidance), places significant emphasis on the spiritual importance of the night preceding Jumu’ah (Friday). While he does not specifically focus on rituals or activities exclusive to Thursday night, he highlights general practices of devotion and worship that are particularly encouraged in Islamic tradition for this time.

Here are some key aspects related to the night of Jumu’ah (Thursday night) as per Islamic teachings, which are also in line with Al-Ghazali’s emphasis on spirituality and devotion:

Increased Dhikr (Remembrance of Allah)

Engaging in the remembrance of Allah through supplications, and recitation of Quran is highly recommended. Imam Al-Ghazali, known for his focus on inner spirituality, would certainly encourage Muslims to intensify their Dhikr during this time.

Performing Extra Prayers (Nawafil)

Although not obligatory, performing additional prayers during this night is seen as a way of drawing closer to Allah and seeking His mercy.

Sending Salutations upon the Prophet Muhammad (Salawat)

This is a common practice encouraged on Thursday nights, aligning with Al-Ghazali’s teachings about following the Sunnah and expressing love and reverence for the Prophet.

Seeking Forgiveness (Istighfar)

The night of Jumu’ah is a time for reflection and seeking forgiveness for one’s sins. Imam Al-Ghazali’s works often discuss the importance of repentance and humility before Allah.

Reading Surah Al-Kahf

It is recommended to read Surah Al-Kahf (the 18th chapter of the Quran) on the night or day of Jumu’ah. This practice, rooted in Hadith, aligns with Al-Ghazali’s emphasis on the benefits of engaging with the Quran.

Making Dua (Supplications)

The night of Jumu’ah is considered a significant time for making Dua, as it is believed that there is a special hour when prayers are more likely to be answered.

Preparing for Jumu’ah Prayer

This includes performing the Ghusl (ritual bath), wearing clean clothes, and using fragrance. Al-Ghazali often emphasizes the importance of physical and spiritual cleanliness in his writings.

The “Barakat”

Traditionally, the gadat was conducted on Thursday evenings and Sundays, but in recent times, it’s more commonly held only on Thursday evenings. The event featured various dishes, including boeber, gadat melk, and melktert. Participants and attendees often received a barakat, or take-home cake, as a token of gratitude.

The frequency of gadats has decreased due to several factors such as the rise of television and social media, the disruption of Muslim communities during Apartheid, and the increase in wealth and materialism within the Muslim population. Today, gadats mostly attract older men, with younger generations being preoccupied with secular and social pursuits. Despite this, maintaining the tradition of gadats, along with other religious rituals like maulood, celebrating mi’araj, and ru’a, is vital. These practices are integral to the Cape Muslim culture, marking its evolution from a history of slavery to its current state and maintaining spiritual awareness.

However, there’s a resurgence of interest in gadats in the Cape Flats, an area plagued by violence and gang activities. For the past three years, Muslim clerics have been working to bring peace to Manenberg and other Cape Town regions. In these areas, an abridged version of the gadat is occasionally held outdoors on Thursday evenings, drawing crowds of up to 200 people. Considering the poverty in these regions, food is provided after the ritual. It is our hope and prayer that Allah Almighty blesses these efforts and that the blessings of the Ratibul Haddaad bring peace, protection, and sustenance to these communities, Insha-Allah.